An excess of quiescent disky galaxies in high-redshift clusters

The GOGREEN Survey: Evidence of an excess of quiescent disks in clusters at 1.0<z<1.4

It is well-established that the environment of a galaxy plays a crucial role in its evolution. In the local universe, galaxies in galaxy clusters are mainly red and no longer forming stars. They have early-type morphologies (a way of saying they are approximately ellipsoidal), which is very different from the disky late-type morphology that star-forming galaxies, like our Milky way, have. This implies a morphological change must have taken place at some point in their lifetime. Understanding when and what drives this morphological transformation is an important question in galaxy evolution.

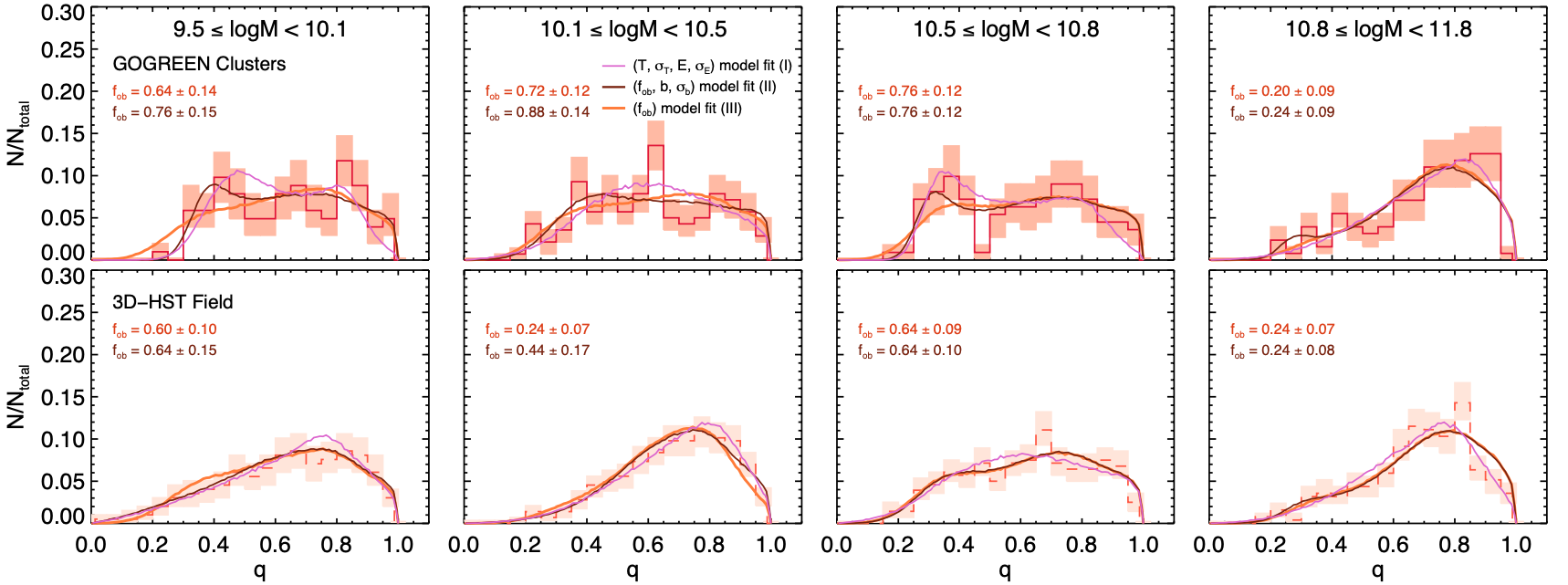

In a study I led in 2021 as part of the Gemini Observation of Galaxies in Rich Early Environments (GOGREEN) survey, I measured the projected axis ratio (the ratio of the minor to the major axis) of cluster galaxies in a sample of galaxy clusters at 1.0<z<1.4 and compared them with a sample of galaxies in the field. Comparing the axis ratio distributions between clusters and the field in four mass bins, the distributions for star-forming galaxies in clusters are consistent with those in the field. But interestingly, the distributions for quiescent galaxies in the two environments are distinct, most remarkably in 10.1<log(M_sun)<10.5 where clusters show a flatter distribution, with an excess at low axis ratios.

Modelling the distribution with oblate and triaxial components, we find that the cluster and field sample difference is consistent with an excess of flattened oblate quiescent galaxies in clusters. The oblate population contribution drops at high masses, resulting in a narrower q distribution in the massive population than at lower masses. Our results suggest that environmental quenching mechanism(s) likely produce a population with a different morphological mix than those resulting from the dominant quenching mechanism in the field.